|

By Yamaoka

As we have now finished up our first month of the new year, we have had a few weeks to apply our 2021 goals in our training. At this point we should have an idea of whether we are doing what we need to do in order to meet those goals. How is your 2021 plan working so far? Have you made any progress? Or are you still running into the same wall? If so, the concept of Genten-Kaiki (going back to basics) may be of use. People use this phrase or concept when they are struggling with a challenge. To achieve a particular goal, people often try a lot of new or different things. But, sometimes despite their best efforts, they find that these things just aren't turning out good results. In such circumstances, we reflect on Genten-Kaiki to clarify for ourselves why we undertook our activity or goal in the first place. From there, we think about what we need in the most basic sense in order to achieve that goal. After doing so, we will often find a solution to our challenge. For Kendo, we try to improve during every Keiko. Ways that we do so include, trying new techniques (Waza), working to bump up our physicality, as well as trying to learn new things from other sports activities, etc., and applying them to our Kendo training. But, sometimes we lose our way in terms of our main purpose. When this happens, often it is because we only focus on Waza, speed or muscle power and neglect Kendo fundamentals. As a result, our Kendo may not be beautiful or attractive in the Budo way because by its appearance alone, it is evident that something is lacking. That missing element is “Balance." Outside of the dojo, people are trying to make a better life for themselves, but sometimes they might switch between “purpose” and “method” while they are looking for what they need. Take for example, someone who loves cars and starts a car business. After several years, the business is highly successful. However, if this person forgets their LOVE of cars, and instead develops a love for money, it might ultimately cost them their business. There are many such examples of this, and they share a failure to balance goal purposes and the methods for achieving them. Going “back to basics” or “back to original motivations” is very important for clarifying who you are. Kendo is the way of the sword and it is a way of life. People sometimes feel lost on their way of life, perhaps because they are exploring a multitude of new things to add to their Kendo. At the time it may feel like they have completely lost their way and created so many detours that the goal is no longer visible. They need to remember their original map, because without it, it creates so many detours that they lose sight of why they went on the journey in the first place. So if you feel lost, consult your original map because it provides you with the path to your original goal. Remember, many times tried-and-true basics are the fastest way to accomplish your goal. This entire new year will present many great opportunities to consider our resolutions. While we do, let's try to go “back to basics”.

0 Comments

By Yamaoka

[Editor's Note: As Musashi said, "From one thing, know ten thousand things." The challenges of the Global Pandemic that we are all going through now might just be a "one thing" that Musashi was talking about. With the right mindset, the Pandemic and our efforts at dealing with it as we continue our keiko, can teach us about life and make us stronger as well. ] As we know, Kendo is "The Way of sword” and is about much more than just fencing. We also know that our keiko experiences can teach us about the Ways of Life outside the dojo. Currently, we are training with restrictions to our keiko, which includes the requirement that we wear masks during keiko. I think almost all people think this is tough because it is hard to breathe and is so hot during the summer. Of course, it is. Our club knows this well. During the pandemic, the regular training venues for our club have closed, and we have graciously been granted floor space at a traditional dojo, that has no air conditioning. After the AUSKF again permitted keiko, we resumed our classes at this dojo. That meant that we had to be willing and able to keiko in our full bogu, with masks, in the Midwest summer heat and humidity. There have been several days when it was over 90 degrees outside, with high humidity, but we adjusted the intensity of our training a bit for safety and trained anyway. Originally Kendo comes from Ken-justu, which differs from Kendo in that it was foremost a skill for killing people in combat with a sword. During those times, as a member of the warrior class, you never knew when the opponent would come for you. So, you had to be prepared to fight in any situation. There were no excuses, just death or life. Therefore, the warrior's keiko had to anticipate and prepare for any kind of "what if?" What if you don’t have shoes and are barefoot in gravel? What if your sword breaks?" What if your are attacked when in a bath? What if you are fighting in the rain and mud? What if it is hot weather and you are fighting in armor? What if ... Let's go back to our present day situation. When we wear a mask, it is hot and hard to breathe. But, what if your very important shiai day or shinsa day is on a hot day with no air conditioning or other cooling and because of that you are short of breath? Is that a good excuse to lose? I am not saying do not push yourself under such circumstances, but I am saying you will have to find out how to adapt and fight effectively in that situation. Because it will be tough to move or strike while you wear the mask, you will have to eliminate wasted movement and find a perfect opportunity to strike. (Older kenshi whose youthful vigor is long gone already know something about this.) A “strong person” does his or her best to prepare for any kind of situation and practices considering all foreseeable and unforeseeable scenarios. We've only been talking about a Kendo situation, but outside the dojo in your work life, you will encounter similar challenges. For example, good businesspersons will do their best to achieve good results in any kind of situation. They strive to turn a negative situation in to a positive one. Effective businesspeople don’t rely on excuses because they know hard times will come someday and they are preparing ahead of time so that later, they don't need excuses. They do that because they just want to succeed. So, let’s take the positive outlook for keiko with a mask. On March 4th, the Omaha Kendo and Iaido Kyokai was honored by a visit from Fumiko Nakajima, sensei, of Japan. Nakajima sensei and two of her students participated in a goodwill keiko at our Wednesday evening class at Benson Community Center. Nakajima sensei is a 6th dan in kendo and an Assistant Professor with the Department of Health and Sports at Niigata University of Health and Welfare. Nakajima sensei is conducting research in the United States regarding attitudes of western kendo practitioners to kendo. Part of her research involved surveys of American kenshi to ascertain whether their motivations and approaches to kendo are as more sport or competition, as a martial art aimed at personal development, or a combination of those and other motivations and approaches. Our members completed surveys and other activities that will be used for her study. Our members had a lively and enjoyable goodwill keiko with Nakajima sensei and her students. Nakajima sensei's beautiful kendo was a treat to experience, and the highlight of the keiko was an exciting match between Nakajima sensei and our teacher, Yamaoka sensei. We look forward to seeing and having keiko again with these kenshi, here or in Japan, and we look forward to reading the result of Nakajima sensei's study. Many thanks to Mariko Anderson, Japanese language teacher at Elkhorn High School and Steve Bills for making this great evening possible. The following story was written by Michael Lindsay, sensei, the head instructor at Shin Sou Fu Kan, a fellow federation dojo located in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Lindsay sensei is one of our kendo pals and frequently honors us by making the long drive to Nebraska for a weekend of kendo with our club. We thank him for sharing his inspiring personal story: I can remember the surgeon telling my mother that I should have been in the intensive care unit. The reason he gave for my not being there was because in this particular wing of the hospital, he was completely in charge and wanted to closely monitor my progression towards recovery himself—with a bit of assistance from the partner of his medical practice. While personal care and direct observation without interference most likely sounds like a positive advantage for someone immediately recovering from their first colectomy, at the time this news could not have made my mother more upset. She heard that I should be in a specialist care unit —a clear indication of where my health stood—and was not. Being that my mother is one of the best in the business, her reaction may be assumed with a reasonable degree of accuracy. She was afraid. Her fears were confirmed over the next few days when a nurse delivered to her the news that I was currently anemic; that the auto-immune suppressants given to me in the weeks before the operation had negatively impacted my body’s ability to heal from the surgery; that I would need regular transfusions of both blood and plasma for the duration of my time in the hospital; that my potassium was perilously low; and that if things did not change in the next eighteen hours I would most likely suffer a stroke from which recovery would be untenable. I don’t remember much past that. “It is easy to kill someone with a slash of a sword. It is hard to be impossible to cut down.” Yagyu Munenori I began the journey that would ultimately save my life in 2004 when I walked through the glass door frame of Sen Shin Kan Martial Arts in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. As a child I always dreamed of fighting dragons and killing giants (it should be noted I still dream of those things), and I had been obsessed with samurai culture ever since I had seen the TV adaptation of Shogun at the recommendation of my benevolent grandmother. Finally, after graduating from high school and following my sweetheart to a Benedictine University about 45 minutes away from the dojo, I would get my chance to learn the swordsmanship of my dreams ... or so I thought. In the years that followed, I gained wonderful opportunities to make new friends and meet new and interesting people. I was able to travel the United States, participating in seminars, tests and tournaments—even reaching a point where I had the great fortune and opportunity of participating in the U.S. National Tournament—and I was lucky enough to forge the defining friendships of my adult life. More than anything, I met my teachers: Abe Koki sensei (Rokudan Renshi) and Iwanami Yoshio sensei (Nanadan Kyoshi) of the Shiku Kai Dojo of Kanagawa, Japan. It would be these two figures who came to represent the Budo values that I had always read about in my childhood, and who to this day epitomize my understanding of the word "Samurai." I could not have known at the time the horrors that waited for me nearly ten years after this original call to adventure—the nightmare-madness of the hospital, the apparent post-mortem of life as I knew it, and the irreparable collapse of both my own image and self-worth to name a few. However, I also could not have known that the truth of those sweat-soaked, blister-laden, soul-crushingly difficult practices with my teacher would indeed equip me to slay the real dragons and giants that emerged along the way. I was not aware that my experiences in Kendo would be a light in that darkness—and that the practice and people of Kendo would restore all I would lose along the way. I could not have known that Kendo would give me back my life. “I believe your ultimate foe is your own self. Your confusion, fears and arrogance may arise. To rebuke them, you need to raise your energy—with a great battle cry.” Kato Shozo, sensei I can remember ignoring the build-up of symptoms for a long time before things got really bad. Having ulcerative colitis is for many an embarrassing condition and I essentially disregarded most of the issues for many years. Eventually, poor life decisions, a bad diet, and stresses at home and work overwhelmed my immune system. I started losing weight rapidly and was eventually placed in the hospital for assessment. The day the colectomy was performed, I had no idea what I was being put under anesthesia for; the doctor had only told me there was air in my torso and he had to find out where it came from. I woke up being held by my doctor and several other nurses in the recovery room to the words, “It was necrotic Michael, we had to take it out,” meaning the entirety of my large intestine. It was the most tremendous pain I had ever experienced. My large intestine had torn in three separate places and subsequently died—spreading infection and peritonitis throughout my abdominal cavity. Worse, the experience in the recovery room itself would leave me with diagnosed post-traumatic stress disorder for years to come. As dark as these events may sound, it is at this moment my experiences with Kendo began to reveal themselves, but not in any way I could have ever imagined. My mother kept asking why the surgeon refused to transfer me to intensive care, and the only answers he would give were that as bad as things were, they could have been worse. He told her that I should not have made it this far, and that “whatever I was doing beforehand had made me tough.” When my physical strength was spent (along with almost 70 lbs.), another facet of Kendo began to influence my days: I started looking at the clock in my room the same way I would look at the clock in my first dojo. I always used to think that every 5 minutes I spent in practice would mean I was 5 minutes better than I was before. In my hospital room, I would do the same between wound dressings or difficult procedures—I’d pick a time five or ten minutes in the future and decide that when the minute hand reached that point, I would feel better. This practice never failed me, and I catch myself doing it in moments of stress even to this day. In this way, I was able to keep my mentality positive during my hospital stay. After the 25th day in the hospital, the surgeon decided I had recovered enough to consider discharging me—albeit under significant aid from home health care. It had taken over 16 combined transfusions of blood and plasma, a week on an NG tube, wound dressings beyond counting, a PICC line, and an ocean of compassion from those closest to me, but I had made it. I was still anemic, but the recovery team established I was stable enough to leave the hospital. I had thought the worst was behind me—and was sadly mistaken. My body was broken, and I had used the extent of my mental and emotional capabilities to cope with the emotional anguish post-operation. It was after being home within the comforts of my old life that my spirit began to erode. Despite the surgeon’s best efforts, the wound would not heal. The site around the surgery wound became infected, and frequent, agonizing dressing and appliance changes were endured on a daily basis. It was in the moments of learning how to change the dressings of the wound where I found the full meaning of the Kendo I had been learning since the bright days of my past. In one of these moments, I remembered Iwanami sensei telling me that Kiai moves into us through our breath rather than just a shout. Kiai was not meant to frighten a cowardly enemy, but rather to bolster our souls—to raise the spirit to quell fear or dismay within oneself. It was in the moments when the nurses (with unwavering compassion and through no fault of their own) were pulling my skin off in the re-dressing process that I imagined my own kiai; coming from deep inside myself like the roaring fire, full in the face of the pain and agony of not only the present, but also the past. If I could not fight my circumstances with my body or mind, I would fight them as best I could with my spirit. “Put your life—your whole life—into your sword.” Abe Koki, sensei At the Shi Ku Kai Dojo in Kanagawa, most everyone uses a tenugui bearing the kanji “Ikken Chi Zai.” When I asked Abe sensei what it meant specifically, he thought carefully for a moment, and with a kind smile gave the words written above. At the time he said these words to me I was young, strong, healthy, arrogant, stupid, stubborn, and completely ignorant of the dangers to which I was willingly subjecting myself. It was not until the full weight of my own choices fell upon me that I understood how these words exemplified the practice of Kendo—and the true value it has for me as a person. Through Kendo I have learned that the ultimate opponent truly lies within all of us—and may only be vanquished by the virtue of the human spirit. Editor's Note: Lindsay sensei's road to recovery was a long one. Over the course of two and a half years, he underwent 7 major procedures, was placed under anesthesia sixteen times, had four major abdominal surgeries, had pneumonia twice and lost approximately 120 pounds. However, in between surgeries, he tested for and passed the kendo yondan shinsa. Since his recovery, he has regained his strength and is again practicing kendo regularly.

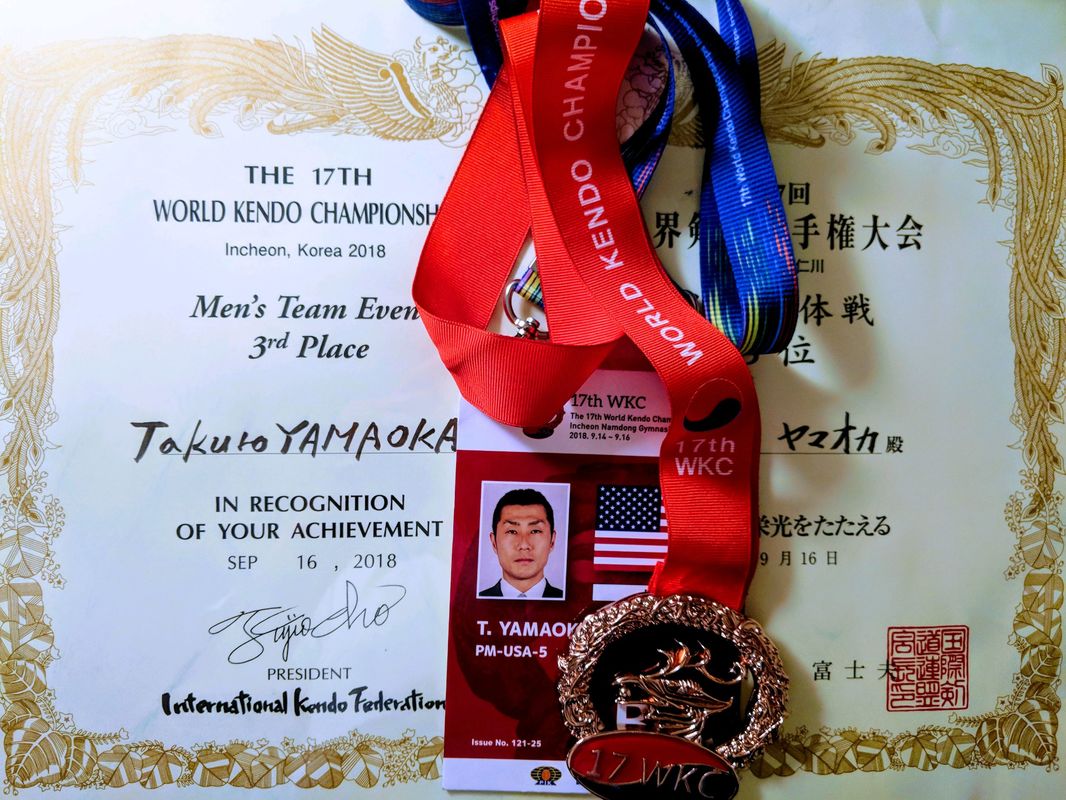

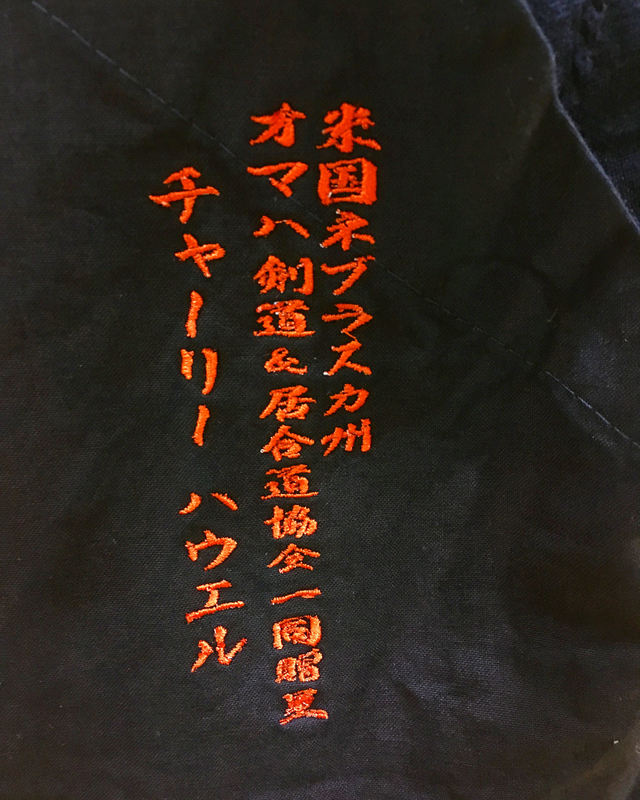

Kendo kata is an integral part of modern Kendo. More important than the fact that it is included in kendo rank testing, the kendo kata embody concepts and techniques that are essential for our shinai kendo remaining and developing as true Kendo. Accordingly, the Fall 2018 Southwest Kendo and Iaido Federation training event opened with a seminar on the kendo kata. Robert Stroud, sensei, (Kendo Kyoshi 7-Dan) led the kendo kata seminar at the Fall Event, held in Omaha, Nebraska, the weekend of October 12-14, 2018. During the seminar, Stroud sensei focused on several important concepts involving both engagement, disengagement, maai and general mindset during the kata. Stroud sensei emphasized that when closing distance in the various kamae, one should not do so in a passive manner. Rather, kenshi should assume kamae and approach at a slightly quicker pace and more importantly, with the "feel" of cautiously closing as though entering an actual sword fight. Accordingly, Stroud sensei also emphasized expression of strong situational awareness at the completion of each kata. As in an actual life and death encounter, Stroud sensei advised uchidachi and shidachi to "disengage gingerly." As kenshi rise in rank, there is an expectation of less reliance upon rote memorization and execution of the kata. Rather, elements such as the specific number of footsteps taken and expression of various maai are increasingly determined by the physical characteristics of the individual practitioners. Stroud sensei noted as an example that just prior to cutting in nihonme, uchidachi should be at uchi-ma, but when each kata is completed, uchidachi and shidachi should be back at shokujin no maii. Throughout the kata, both uchidachi and shidachi will be adjusting the length of their steps. So instead of just focusing on the number of steps in kata, we should consider how close or far we need to be from the opponent during different stages in kata, and position ourselves as the situation dictates. In addition to the spatial aspect of combative engagment distance, the temporal interval was also addressed. Stroud sensei noted that the interval between "yaa" and "tou" is to be such that it corresponds to a vigorous, rapid cut by shidachi in response to uchidachi's attack. Again, the idea of realistic adaptation and response to the situation was reinforced. This is akin to execution of techniques such as oji-waza in shinai kendo, whereby the opponent's sword/cut is parried and immediately followed with a counter without waiting, delay, rocking back on one's heels, or otherwise breaking "connection" or seme. Stroud sensei also provided several corrections or tips for specific portions of the kata. One notable example was the shidachi's response to uchidachi's thrust to the left lung during sanbonme. Rather than a hooking redirection with the mune of shidachi's sword, shidachi instead utilizes nayashi waza (tsuki nayashi tsuki) in order to neutralize the incoming thrust and counter attack. Shidachi neutralizes the tsuki (rendering it ineffective) by redirecting it to their left and down (see photos below). Stroud sensei also emphasized that while doing so, shidachi must not allow her left hand to pull away from her center. Finally, Stroud sensei discussed the progressing skill or even nobility of action demonstrated by the kenshi, during the kata, particularly in the first three longsword kata. The conclusion of these three kata show the development of ability and sophistication of the swordsman from lethal dispatch of the attacker in ipponme; de-fanging the attacker with an injurious cut in nihonmne; and finally defeating the attacker without injury in sanbonme. In a way, this was a recurring theme that could be found throughout the seminar; i.e., that over the years, as our understanding and skill at kendo increases, our execution of its waza will evolve as well.  Yamaoka sensei/Team USA #5 on September 16, 2018, at the 17th World Kendo Championships. (photo by www.kendo.photography) Yamaoka sensei/Team USA #5 on September 16, 2018, at the 17th World Kendo Championships. (photo by www.kendo.photography) Takuro Yamaoka, sensei, the leader of the Omaha Kendo and Iaido Kyokai, recently returned from South Korea, where he competed as a member of Team USA at the 17th World Kendo Championships. Yamaoka sensei participated as a member of the five-man team that won bronze medals in the team competition. Team USA's Men's Team defeated the teams of four other countries (Serbia, Croatia, Italy and Singapore) before being defeated by Korea, the team that would ultimately win the silver. The final results of the team competition were Japan winning the gold in the team competition, Korea the silver and the United States and Chinese Taipei both winning the bronze. The Men's Individual Champion was Sho Ando of Japan. The Women's Individual Champion was Mizuki Matsumoto of Japan. The 17th World Kendo Championships were held in Incheon, South Korea, from September 14-16, 2018, and featured competition among teams from 52 countries. The United States was represented at the WKC by a contingent of male and female kenshi who competed in the men's individual, women's individual and men's team competitions. Team USA was led by the following senseis: Delegation Leader Yuji Onitsuka; Delegation Managers Chis Yang and Shuntaro Shinada; and Coaches Brandon Harada and Daniel Yang. Yamaoka sensei was selected for the team in 2017 after a series of highly-competitive try-outs that drew team prospects from across the United States. Yamaoka sensei and his teammates participated in numerous challenging workouts held in California and Texas, as well as in other countries, including France and Japan, all in preparation for the World Championships. Hundreds or even thousands of kendo practitioners worldwide train for decades in order to gain a spot on their highly-selective national teams. All of this effort and dedication condenses down into the WKC matches that are three points or four minutes maximum, during a global tournament that is only held every three years. As a result, the WKC features kendo at a very high level of intensity. Congratulations to Team USA for again doing an excellent job of representing the United States at the World Kendo Championships! Recently, members of our iaido class made the trek to Fargo, North Dakota, for the iaido seminar hosted by Anderson, sensei, and the Agassiz dojo. Pam Parker, sensei, (iaido nanadan) of New York’s Ken Zen dojo, once again led the seminar. Xanto putting up a fight. In order to complete the seven-hour land journey from Nebraska to the seminar, we first had to cross through a spring blizzard that had been named “Xanto” by the weather service. Xanto was an intimidating storm that was not to be taken lightly, and at times reduced road conditions down to zero visibility. Eventually, Xanto’s blowing and accumulating snow and sleet caused closure of Interstate 29, and one of our members was stranded at a filling station and had to wait out the storm overnight in his car. Clearing the north edge of Xanto However, by the next day, our members arrived in Fargo and were suited up, swords oiled and on the training floor ready to go. On the floor as well were members of Des Moines Iaido, including their leader, Flinn sensei. Their drive to the seminar had been even longer than our own. Parker sensei shared numerous insights and details regarding Seitei iaido - the twelve standardized forms of the All Japan Kendo Federation. However, Parker sensei also discussed the equally (and some would say “more”) important topic of etiquettes and courtesies found in Būdō, which go beyond the opening and closing formalities of our practice. A major point being that these qualities should permeate everything we do, in the course of our practice. It was noted that higher level senseis would be able to see the presence or absence of these qualities in our actions. Similarly, to such an informed eye, our individual personalities would be revealed in our execution of the forms. That’s something to think about both on and off the dojo floor. The seminar was well worth the drive required to attend it. Our sincere thanks to Parker and Anderson senseis, and to the Agassiz Dojo for their time and efforts that made it a top-notch training.

For more information about Parker sensei, please read her excellent article, courtesy of George M. and Kenshi 24/7: https://kenshi247.net/blog/2015/02/09/bowing-to-the-7/ The OKIK was in attendance at the Idaho Iaido Seminar this past weekend. The seminar featured world-class teachers and gave attendees the opportunity to receive excellent instruction in both modern and classical Iaido forms as well as Kendo.

The seminar was hosted by Robert Stroud sensei and the Idaho Kendo Club. Instruction at the seminar was provided by Konno sensei (Seattle), Stroud sensei (Boise), Seto sensei (Seattle), Ichimura sensei (Dallas), Olson sensei (Washington), and Hankins sensei (Salt Lake City). It is often said that Kendo and Iaido are two wheels on the same cart, and this seminar provided a rare opportunity for instruction and competition in both arts. The weekend featured Kendo keiko and post-keiko feedback from senseis and a full-fledged Iaido seminar. Finally, a unique combined Iaido and Kendo tournament capped off the multi-day training. A highlight of the tournament was a thrilling Kendo match between the Atagi Brothers (both instructors at Boise State Uviversity Kendo Club). In addition to the excellent, high-intensity Kendo of senseis Atagi, the match featured a fascinating matchup of nito (two sword style) versus jodan (overhead guard). The OKIK looks forward to the 2019 Boise Iaido Seminar.

Hidehisa Nishimura of Kumamoto claimed first place at the 65th All Japan Kendo Championship on November 3rd at the Tokyo Bodukan. This video features the final match between Nishimura and Ryoichi Uchimura of Tokyo. This is Nishimura's second time winning the championship at only 28 years old—you can see why in the first video below! For years, Nishimura has idolized Uchimura and has worked hard to develop his own version of Uchimura’s style of kote attack. Nishimura used that very attack to win the match with his long-time hero, Nishimura. Uchimura observed kendo etiquette, and showed little or no emotion, during what must have been a pinnacle moment in his young life. Similarly, Nishimura showed grace and dignity after the match, as the two calmly removed and bound up their gear. At the time the match originally aired, observant viewers, fluent in Japanese heard the announcer describe Nishimura and Uchimura's acknowledgement of one another after immediately after the match: “[t]hey looked for each other and Uchimura looked like he gave Nishimura some sign. It appears that at that Uchimura says to Nishimura, “well done” (よくやった。). This is a good example of the rich subtleties of the Būdō, that are largely hiding in plain sight.” For more info, check out the All Japan Kendo Federation website. |