|

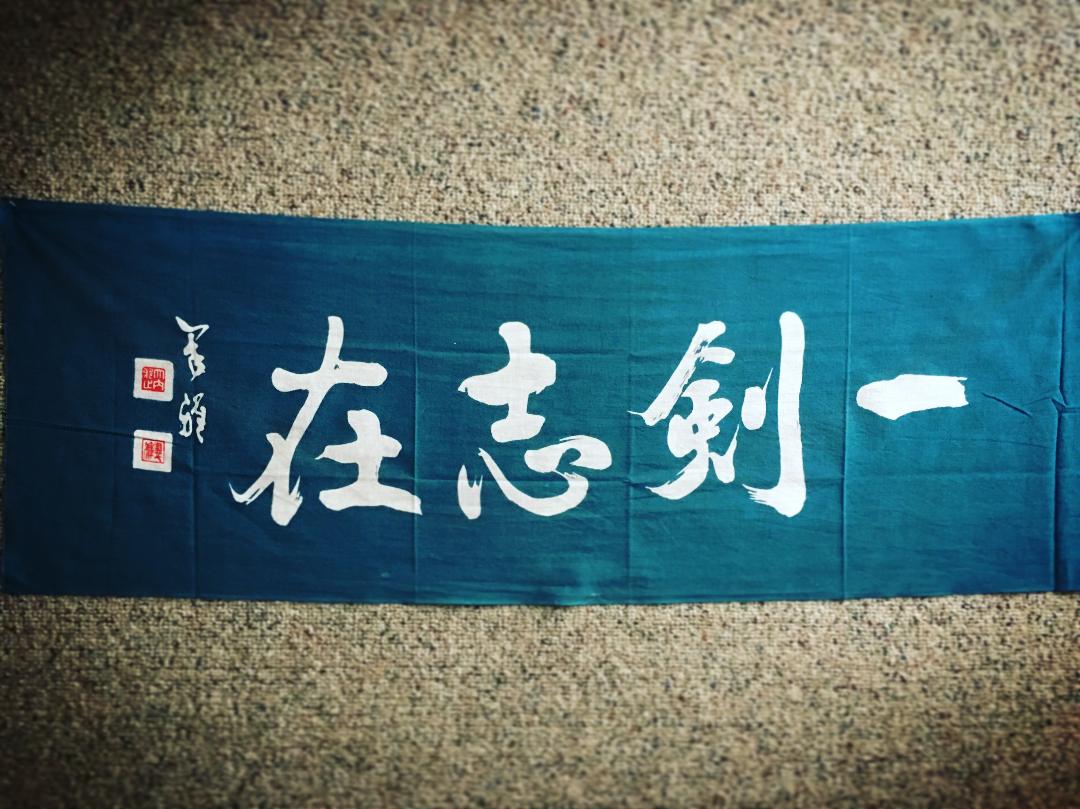

The following story was written by Michael Lindsay, sensei, the head instructor at Shin Sou Fu Kan, a fellow federation dojo located in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Lindsay sensei is one of our kendo pals and frequently honors us by making the long drive to Nebraska for a weekend of kendo with our club. We thank him for sharing his inspiring personal story: I can remember the surgeon telling my mother that I should have been in the intensive care unit. The reason he gave for my not being there was because in this particular wing of the hospital, he was completely in charge and wanted to closely monitor my progression towards recovery himself—with a bit of assistance from the partner of his medical practice. While personal care and direct observation without interference most likely sounds like a positive advantage for someone immediately recovering from their first colectomy, at the time this news could not have made my mother more upset. She heard that I should be in a specialist care unit —a clear indication of where my health stood—and was not. Being that my mother is one of the best in the business, her reaction may be assumed with a reasonable degree of accuracy. She was afraid. Her fears were confirmed over the next few days when a nurse delivered to her the news that I was currently anemic; that the auto-immune suppressants given to me in the weeks before the operation had negatively impacted my body’s ability to heal from the surgery; that I would need regular transfusions of both blood and plasma for the duration of my time in the hospital; that my potassium was perilously low; and that if things did not change in the next eighteen hours I would most likely suffer a stroke from which recovery would be untenable. I don’t remember much past that. “It is easy to kill someone with a slash of a sword. It is hard to be impossible to cut down.” Yagyu Munenori I began the journey that would ultimately save my life in 2004 when I walked through the glass door frame of Sen Shin Kan Martial Arts in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. As a child I always dreamed of fighting dragons and killing giants (it should be noted I still dream of those things), and I had been obsessed with samurai culture ever since I had seen the TV adaptation of Shogun at the recommendation of my benevolent grandmother. Finally, after graduating from high school and following my sweetheart to a Benedictine University about 45 minutes away from the dojo, I would get my chance to learn the swordsmanship of my dreams ... or so I thought. In the years that followed, I gained wonderful opportunities to make new friends and meet new and interesting people. I was able to travel the United States, participating in seminars, tests and tournaments—even reaching a point where I had the great fortune and opportunity of participating in the U.S. National Tournament—and I was lucky enough to forge the defining friendships of my adult life. More than anything, I met my teachers: Abe Koki sensei (Rokudan Renshi) and Iwanami Yoshio sensei (Nanadan Kyoshi) of the Shiku Kai Dojo of Kanagawa, Japan. It would be these two figures who came to represent the Budo values that I had always read about in my childhood, and who to this day epitomize my understanding of the word "Samurai." I could not have known at the time the horrors that waited for me nearly ten years after this original call to adventure—the nightmare-madness of the hospital, the apparent post-mortem of life as I knew it, and the irreparable collapse of both my own image and self-worth to name a few. However, I also could not have known that the truth of those sweat-soaked, blister-laden, soul-crushingly difficult practices with my teacher would indeed equip me to slay the real dragons and giants that emerged along the way. I was not aware that my experiences in Kendo would be a light in that darkness—and that the practice and people of Kendo would restore all I would lose along the way. I could not have known that Kendo would give me back my life. “I believe your ultimate foe is your own self. Your confusion, fears and arrogance may arise. To rebuke them, you need to raise your energy—with a great battle cry.” Kato Shozo, sensei I can remember ignoring the build-up of symptoms for a long time before things got really bad. Having ulcerative colitis is for many an embarrassing condition and I essentially disregarded most of the issues for many years. Eventually, poor life decisions, a bad diet, and stresses at home and work overwhelmed my immune system. I started losing weight rapidly and was eventually placed in the hospital for assessment. The day the colectomy was performed, I had no idea what I was being put under anesthesia for; the doctor had only told me there was air in my torso and he had to find out where it came from. I woke up being held by my doctor and several other nurses in the recovery room to the words, “It was necrotic Michael, we had to take it out,” meaning the entirety of my large intestine. It was the most tremendous pain I had ever experienced. My large intestine had torn in three separate places and subsequently died—spreading infection and peritonitis throughout my abdominal cavity. Worse, the experience in the recovery room itself would leave me with diagnosed post-traumatic stress disorder for years to come. As dark as these events may sound, it is at this moment my experiences with Kendo began to reveal themselves, but not in any way I could have ever imagined. My mother kept asking why the surgeon refused to transfer me to intensive care, and the only answers he would give were that as bad as things were, they could have been worse. He told her that I should not have made it this far, and that “whatever I was doing beforehand had made me tough.” When my physical strength was spent (along with almost 70 lbs.), another facet of Kendo began to influence my days: I started looking at the clock in my room the same way I would look at the clock in my first dojo. I always used to think that every 5 minutes I spent in practice would mean I was 5 minutes better than I was before. In my hospital room, I would do the same between wound dressings or difficult procedures—I’d pick a time five or ten minutes in the future and decide that when the minute hand reached that point, I would feel better. This practice never failed me, and I catch myself doing it in moments of stress even to this day. In this way, I was able to keep my mentality positive during my hospital stay. After the 25th day in the hospital, the surgeon decided I had recovered enough to consider discharging me—albeit under significant aid from home health care. It had taken over 16 combined transfusions of blood and plasma, a week on an NG tube, wound dressings beyond counting, a PICC line, and an ocean of compassion from those closest to me, but I had made it. I was still anemic, but the recovery team established I was stable enough to leave the hospital. I had thought the worst was behind me—and was sadly mistaken. My body was broken, and I had used the extent of my mental and emotional capabilities to cope with the emotional anguish post-operation. It was after being home within the comforts of my old life that my spirit began to erode. Despite the surgeon’s best efforts, the wound would not heal. The site around the surgery wound became infected, and frequent, agonizing dressing and appliance changes were endured on a daily basis. It was in the moments of learning how to change the dressings of the wound where I found the full meaning of the Kendo I had been learning since the bright days of my past. In one of these moments, I remembered Iwanami sensei telling me that Kiai moves into us through our breath rather than just a shout. Kiai was not meant to frighten a cowardly enemy, but rather to bolster our souls—to raise the spirit to quell fear or dismay within oneself. It was in the moments when the nurses (with unwavering compassion and through no fault of their own) were pulling my skin off in the re-dressing process that I imagined my own kiai; coming from deep inside myself like the roaring fire, full in the face of the pain and agony of not only the present, but also the past. If I could not fight my circumstances with my body or mind, I would fight them as best I could with my spirit. “Put your life—your whole life—into your sword.” Abe Koki, sensei At the Shi Ku Kai Dojo in Kanagawa, most everyone uses a tenugui bearing the kanji “Ikken Chi Zai.” When I asked Abe sensei what it meant specifically, he thought carefully for a moment, and with a kind smile gave the words written above. At the time he said these words to me I was young, strong, healthy, arrogant, stupid, stubborn, and completely ignorant of the dangers to which I was willingly subjecting myself. It was not until the full weight of my own choices fell upon me that I understood how these words exemplified the practice of Kendo—and the true value it has for me as a person. Through Kendo I have learned that the ultimate opponent truly lies within all of us—and may only be vanquished by the virtue of the human spirit. Editor's Note: Lindsay sensei's road to recovery was a long one. Over the course of two and a half years, he underwent 7 major procedures, was placed under anesthesia sixteen times, had four major abdominal surgeries, had pneumonia twice and lost approximately 120 pounds. However, in between surgeries, he tested for and passed the kendo yondan shinsa. Since his recovery, he has regained his strength and is again practicing kendo regularly.

1 Comment

|